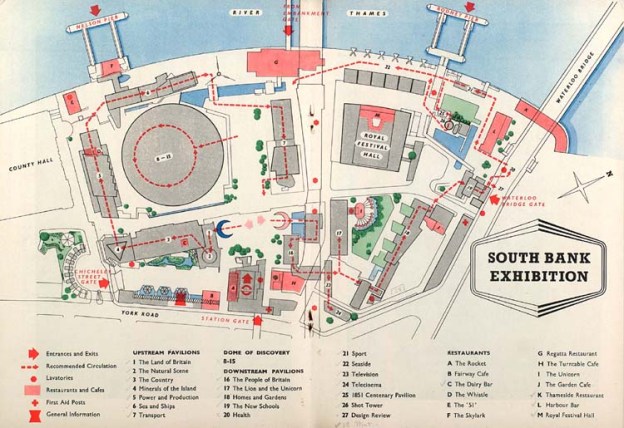

Few events of the last century brought art and the public together quite as dramatically as the Festival of Britain, with an estimated 8 ½ million people visiting London’s South Bank alone between 3 May and 30 September, 1951. Littered among the pavilions – stuffed to their elegantly-domed roofs with artefacts and accolades – and strewn among the lawns and pathways of Battersea Pleasure Gardens were more than 30 sculptures and 50 murals. This was a programme of fine art quite distinct from the thousands of other objects on display and (although grouped together in the catalogue) from Powell & Moya’s more architectural Skylon. Added to this, many of the galleries in the capital organised exhibitions to coincide with the Festival, from the folk art of ‘Black Eyes and Lemonade’ at the Whitechapel Gallery to the exploration of art and science that was ‘Growth and Form’, organised by artist Richard Hamilton and biologist Lancelot Law Whyte at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. Victor Pasmore – whose spiral mural, glazed into the tiles of the Regatta Restaurant, is one of the abiding visual memories of the South Bank Exhibition – identified a ‘creative explosion in the visual arts which spread throughout the world following the renewal of free expression after the war,’(1) leading to the influx of many mature students to art school and making contemporary visual art difficult to ignore in a thorough consideration of national culture. But, enmeshed in the discussion around the commissioning of artworks for the Festival of Britain are problems that continue to face commissioners of contemporary art.

As an undertaking, the Festival was undeniably ambitious, a phenomenal achievement considering the time and resources available. Early on in the planning process, it was decided that ‘as far as possible the organisers of the Festival should be professional architects, designers, engineers etc. and not professional arts administrators’. (2) Gerald Barry – who resurrected the original suggestion for a Festival (3) in an open letter to Sir Stafford Cripps (President of the Board of Trade) published in the left-wing News Chronicle – was appointed Director General and Hugh Casson Director of Architecture. With a co-ordinator employed to attend to more pragmatic logistical details, an anti-bureaucratic, maverick spirit was nurtured within the Festival Committee, described as having ‘a healthy horror of red tape, [whereas] the civil servants who were appointed to the Festival were not always able to cut themselves free of its entanglements’. (4) With the Festival Committee commissioning and co-ordinating some 50 architects – all under 45, none of whom had built anything bigger than a house – attempts were made to encourage the architects to invite artists to collaborate with them. This saw Jane Drew, architect of the Riverside Restaurant and one of the few women involved in the Festival, commissioning a mural from Ben Nicholson for her building. (5)

The Festival represented an important milestone in state support of the arts. Having evolved from the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA) in the aftermath of the war, the Arts Council commissioned new work from Jacob Epstein, Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore – the three best known of the twelve sculptors who would be included in the South Bank Exhibition – with a budget of £5,000. The Arts Council also initiated the ‘60 Paintings for 51’ touring exhibition, eventually buying five works for its collection at £500 each. There is evidence that the Festival Design Group (specifically Hugh Casson and Misha Black who had an interest in contemporary art) reluctantly took the lead on commissioning the remaining sculptures from lesser-known artists for a total of under £10,000, including production costs, which represented only around 0.2% of Festival expenditure. (6) There is little evidence that high profile triumphalism was matched by investment at the grassroots level to nurture future talent, through incremental steps that do not benefit from a major fanfare. To some extent, then, art seems to have been an afterthought, reflected in the haphazard commissioning process and the paltry allocation of budgets.

Conceived as a narrative experience according to certain themes – loosely divided into ‘The Land’, ‘The People’ and ‘Discovery’(7) – the Festival involved writers like Laurie Lee to draft the story that would be conveyed, through guides and captions, in a vaguely educational, paternalistic approach that was roundly dismissed a quarter of a century later: ‘As an exhibition the South Bank was a failure. The thematic treatment fought with the exhibits and the whole was too indigestible for the visitor to absorb. And the exhibition itself as a communications technique was already on the way out, displaced by better colour printing, easier travel and – above all – TV’. (8)

Pre-emptively disarming accusations of London-centrism, the Festival was intended to have a presence throughout the United Kingdom. However, regional manifestations received no central funding and generally took the form of modest civic improvements and sporadic cultural events. Leeds was one of four regional cities that played host to the Land Travelling Exhibition, which required a 40,000 square foot tented structure to be erected at its Woodhouse site and attracted 144,844 visitors. With an emphasis on industrial design, this provided in concentrated form the same kind of narrative as in London, examining Britain’s skills, resources and pioneering spirit.

It would seem to have been the intention of the organisers that the architecture, art, landscape and design on the South Bank would work together in a glorious democratic unity to complement the grand narrative. The catalogue refers to ‘the theme of the Exhibition [being] illustrated in many places within the Pavilions by new works specially commissioned from artists, sculptors and designers’.(9) Artists commissioned by the Arts Council were simultaneously advised of the main Festival themes and exempted from the responsibility of adhering to them. The art historian Robert Burstow has subsequently identified many thematic links between the content and location of artworks and the Festival at large, including those from the Arts Council sculptors, with art largely rendered subordinate to the architecture.

Perhaps the biggest pitfall of Festival art commissioning was its prescriptive nature; the expectation that artists would respond to a theme is inherently flawed and can only ever lead to the artist’s intentions being compromised. This approach arguably prefaced the instrumentalisation of art by successive Governments, which has most recently seen public funds ring-fenced for priorities like social inclusion ‘premised on the top-down ‘democratisation’ of culture, a process aimed at engaging members of ‘excluded’ groups in historically privileged cultural arenas. Such a policy neither reforms the existing institutional framework of culture, nor reverses a process of damaging privatisation. Instead, it attempts to make the arts more accessible in order to adapt its target audiences to an increasingly deregulated labour market’. (10)

Relatively untrammelled by bureaucracy, the men culled from the ruling classes to give their impression of Britain through the medium of the Festival were afforded an unprecedented amount of creative freedom. Rather than exploiting this potential to pioneer creative developments for the future, they reverted to the safe territory of the Establishment. Indeed, eight other more controversial (read: abstract) sculptures commissioned by the Arts Council were declined for the South Bank Exhibition by Hugh Casson.(11) As a testament to this attitude, Misha Black, one of the most proactive commissioners of art from the Design Group, later reflected on the success of visual art that tended towards explicit subject matter and aesthetic convention: ‘The moral of this art/architectural activity was, I now feel sure, that art only has impact on large sections of the community when its subject is deeply emotive and when it is at the same time of such aesthetic consequence that no one can contemplate it without empathic involvement. I fear that few of the works of our artist colleagues simultaneously met both criteria’.(12)

A clear rift seems discernible between the ‘moderate modernism’ advocated by the organisers – which was evident in the architecture they sanctioned that borrowed heavily from the accepted International Style – and the more experimental commissioning policy of the fledgling Arts Council ‘whose officers saw their responsibilities primarily in terms of stimulating public interest in what they regarded as the best modern art, unlike the Festival authorities who were more sceptical of the suitability of modernism to ‘the People’s Show’’. (13)

Although the Festival was intended as a non-partisan affair it quickly became synonymous with the Labour Government in general and with Herbert Morrison (14) in particular. There is an old adage that those on the left-wing believe art to be elitist whereas those on the right consider it to be subversive. And so it was, in the years after World War II, that the commissioning of art for the Festival of Britain became politicised, with a London-based art critic commenting:

Naturally the figurative artists came off best in the public arena. For the only occasion in my experience painting and sculpture became even the tiniest bit proletarian in the sense that people read contemporary work without the help of pseudo-philosophical interpretations by superfluous critics. (15)

That legibility was equated with accessibility in the critical response to Festival artworks allows only for an art that appeals to the senses but fails to engage the brain. Despite decades of conceptual art, this expectation has proven stubborn to displace and forms part of a misguided anti-intellectual tradition in Britain that has paved the way for a legacy of incomprehension. The gulf between audiences and artists gapes ever wider with top-down efforts, from the Festival of Britain onwards, failing to incite the public imagination and systemic problems within education doing little to foster better understanding.

Michael Frayn would later identify two opposing camps that developed around the Festival across party lines: the Carnivores, (16) who rabidly contested the achievements of the Labour Government – and included ‘a small number of puritan left-wingers who, not without good reason, saw the Festival as an example of middle-class social democracy in action, with no opportunity whatsoever for the participation of the working class, the ‘People’ in whose name the Festival was created’ (17) – and the Herbivores, the ‘radical middle classes […] gentle ruminants, who look out from the lush green pastures which are their natural station in life with eyes full of sorrow for less fortunate creatures, guiltily conscious of their advantages though not usually ceasing to eat the grass’. (18) Despite their apparent differences, common ground between the two groups can be found in their acceptance of the status quo and its manifestation in the Festival. It was felt that ‘if artists’ styles and/or politics were too extreme, they risked transgressing the mythical national tradition’. (19) At a basic level, there was a negation of the transformative power of art in effecting social change from the ground up, perhaps motivated by fear of dissent in a fragile nation. Ultimately, Festival art was a platitude, supplementing a vision imposed from on high.

Carried on the winds of change whipped up by the Festival were the seeds of gentrification, the ‘moderate modernism’ perpetuated in towns and cities around Britain. Viewed from the vantage point of the early 21st century, the most radical philosophy underpinning the Festival was the provision of non-commercial public space that it was hoped would ensure the survival of democracy and prevent the rise of totalitarianism. (20) But, there is little evidence that the transient Festival had any lasting impact in the field of visual art. No deviations or challenges were made to the existing order, no new benchmarks were set and no new genres arose.

More than half a century after this landmark project, the visual culture that could only be imagined in 1951 has been thoroughly consolidated, with thousands of images a second beamed at us in our homes and in our public spaces. It is interesting to speculate on what would have happened if the Arts Council had succeeded in capitalising on the public attention for the Festival by bringing new and challenging art to the public instead of allowing the organisers to pander to mediocre expectations. Visually literate generations might have been spawned, armed with new tools to navigate complex stimuli. Contrary to the teachings of the Festival, great achievements are not only made in the fields of industry, science and technology. Only a capacity for creative and critical thinking, engendered in part by visual art, will allow the world to be re-imagined for the future and it is here, with the vestiges of public funding, that scope still exists for revolution.

Commissioned by Leeds Festival, 2005.

__________________________________________________________

1. Victor Pasmore, ‘A Jazz Mural’ in Mary Banham & Bevis Hillier (eds), A Tonic to the Nation: The Festival of Britain 1951 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1976), p. 102

2. Adrian Forty, ‘Festival Politics’ in Ibid, p. 37.

3. Made by the Royal Society of Arts to Government in 1943

4. Anthony D. Hippisley Coxe, ‘I enjoyed it more than anything in my life’ in A Tonic to the Nation op cit, p.88.

5. Jane Drew, ‘The Riverside Restaurant’ in Ibid, p. 103

6. Robert Burstow. ‘Modern Sculpture in the South Bank Townscape’ in Elain Harwood and Alan Powers (eds), Festival of Britain (London: Twentieth Century Society, 2001).

7. Ian Cox, The South Bank Exhibition: A guide to the Story it Tells (London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1951), pp. 4-5:

‘The Land’: The Land of Britain, The Natural Scene, The Country, Minerals of the Island, Power and Production, Sea and Ships, Transport

‘The People’: The People of Britain, The Lion and the Unicorn, Homes & Gardens, The New Schools, Health, Sport, Seaside.

‘The Dome of Discovery’: The Land, The Earth, Polar, Sea, Sky, Outer Space, The Physical World, The Living World

8 . Charles Plouviez, ‘A minor mannerism in art history’ in A Tonic to the Nation op cit, p. 166.

9 . See Cox, op.cit, p. 90.

10. Cultural Policy Collective, Beyond Social Inclusion: Towards Cultural Democracy, 2004.

11. One of these sculptures, by Bernard Meadows, found its way to Battersea, the remaining seven touring with the ‘60 Paintings for ‘51’ exhibition

12. Misha Black, ‘Architecture, Art and Design in Unison’, in A Tonic to the Nation op cit, p. 84.

13. Robert Burstow. ‘Modern Sculpture in the South Bank Townscape’ in Elain Harwood and Alan Powers (eds), Festival of Britain (London: Twentieth Century Society, 2001), p. 99.

14. Morrison served as both deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary to the post-war Labour Government during the planning of the Festival and became known as ‘Lord Festival’.

15. GS Whittet, ‘Encouragement for Artists’ in A Tonic to the Nation op cit, p. 181.

16. Churchill is said to have been the most vocal of the Carnivores. To ease this tension General Ismay, Churchill’s Chief of Staff, was appointed Chairman of the Festival Committee.

17. Forty, op cit, p. 29.

18. Michael Frayn, ‘Festival of Britain’ in Michael Sissons & Philip French (eds), Age of Austerity (London: Hodder and Stourton, 1963).

19 . Burstow, op cit, p. 106.

20. Burstow, op. cit, p. 106.